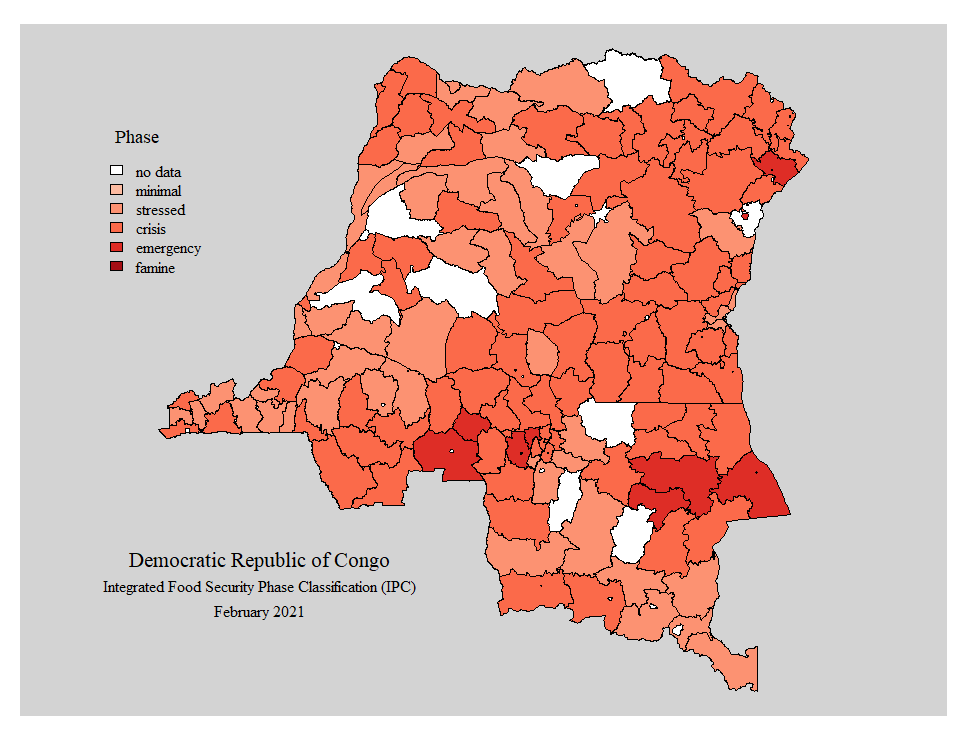

Map 3: Democratic Republic of Congo food security | 6th Nov 2021

Claire Dooley

#30DayMapChallenge theme: red

Data

- The IPC Population Tracking Tool (IPC, 2021; http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/population-tracking-tool/en/)

- UNOCHA boundaries (UNOCHA, 2019; https://data.humdata.org/dataset/drc-administrative-boundaries-levels-0-2)

Code

Map code available on GitHub

I used the sf package (Pebesma, 2018) to convert data into an easy-to-use format, and the RColorBrewer package for the colour palette (Neuwirth, 2014).

About the map

The map above shows the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) for subnational units of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), for February 2021. The IPC categorises regions as either minimal, stressed, crisis, emergency or famine. Nine of DRC’s unit were classification as emergency and a further 86 as crisis. In DRC, food security is driven in part by armed conflict that threatens civilians’ lives, restricting their access to agricultural land and/or causing them to flee. In February 2021, DRC had 5.7 million people in the emergency category. Other countries with at least one million people categorised in emergency or famine are Yemen, Afghanistan, Nigeria, South Sudan, Venezuela, Sudan, Ethiopia and Haiti.

The IPC is intended to be a clear and simple dataset for strategic decision-making. The IPC provides information not only on the severity of food insecurity subnationally but also estimates of the number of people affected. More information about the classification procedure and how it’s used for decision-making and response planning can be found in the IPC Technical Manual (IPC Global Partners, 2021). The IPC stands as the basis for much of the World Food Programme’s (WFP) humanitarian work. WFP’s 2021 Global Operational Response Plan provides regional and country level summaries of food and nutrition security as well as the actions needed to remedy the impacts of conflict, climate change and socioeconomic consequences of COVID-19.

Linking dataset based on geography is mostly done by either: 1) matching geometry information, e.g. overlapping coordinates or areas; 2) matching place names; or 3) matching administrative unit codes. For the image above, I matched the administrative unit names to link the IPC data to the boundaries data, as the IPC data doesn’t include geometries or coordinates and the unit IDs/codes in the two datasets followed different coding systems. Matching different spatial datasets is often challenging because of differences in naming conventions, coding systems and boundary delineation. Here, there were a handful of unit names that differed between the datasets, e.g. ‘Territoire de LODJA’ and ‘Lodja’, and the IPC data included 24 separate units within Kinshasa whereas the boundaries data had a single unit for Kinshasa. The break-down of IPC classifications for subunits across Kinshasa is really useful (if they can be linked to information about where those units are) as finer scale information can help refine the action needed, targetting those most at risk.

Harmonising boundaries and unit identifiers can be complex and sensitive. For more information on work in this area being carried out under the grid3 programmes in DRC, Nigeria and Zambia, see here (CIESIN et al. 2020).

Citations

- IPC. (2021). “The IPC population tracking tool”. Data downloaded on 06/11/2021 from http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/population-tracking-tool/en/

- UNOCHA. (2019). “Democratic Republic of the Congo (COD) Administrative Boundary Common Operational Database (COD-AB)”. Data downloaded on 06/11/2021 from: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/drc-administrative-boundaries-levels-0-2

- Pebesma, E. (2018). “Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data.” The R Journal, 10(1), 439–446. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2018-009

- Neuwirth, E. (2014). “RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer Palettes. R package version 1.1-2” https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RColorBrewer

- IPC Global Partners. (2021). “Integrated Food Security Phase Classification Technical Manual Version 3.1. Evidence and Standards for Better Food Security and Nutrition Decisions.” Rome. http://www.ipcinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/manual/IPC_Technical_Manual_3_Final.pdf

- Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University; Flowminder Foundation; United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA); WorldPop, University of Southampton. (2020). “Harmonising Subnational Boundaries”. Palisades, NY: Georeferenced Infrastructure and Demographic Data for Development (GRID3). https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-k3h9-sf83. Accessed 06/11/2021

License: CC BY

Back to main